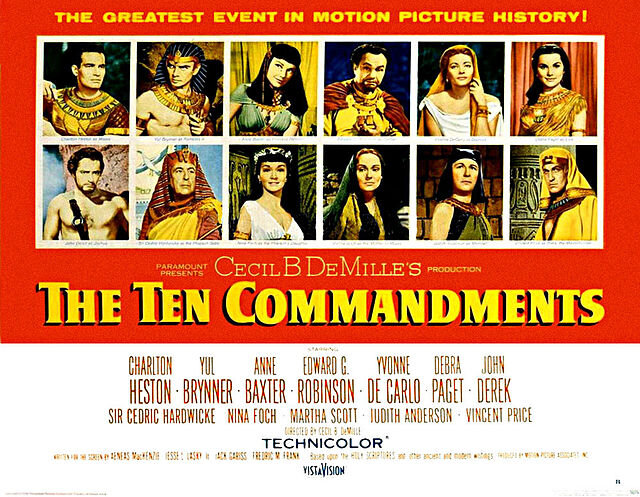

When I was seventeen my dad died, but before that, every year we’d celebrate Easter by watching The Ten Commandments. I’d be lying if I didn’t say it was my favorite day of the year. Four to six—depending on the network and thus the frequency of commercials—uninterrupted hours on the couch with my dad, my sister, and my fourth favorite story from the Bible. If he remembered, he’d get us popcorn from the CVS down the street. We’d all pass around the giant terra cotta bowl my mother usually only let us touch on holidays, and chow down as Charlton Heston hammed it up on screen.

Every year it was as if we were watching the movie for the first time. My dad would gasp, shake his head, and clap through each plague God imposed on the Egyptians through Moses. My sister and I cried every single time we saw the Pharoah’s horses drown in the parted Red Sea. Most years, when Moses came down from the mountain and saw the decadence the people of Israel had succumbed to, I saw my dad let out a few silent tears.

As I type this, I’m watching the movie with my niece. We are gawping at the shaved-head-side-pony-combo Pharoah Ramses’ son is rocking. She tells me that boys in this generation would think it’s weird that all the guys in this movie are wearing dresses and skirts and sandals. I am thinking about how camp all of this as the story of Passover begins to “pass over” (I’m so, so sorry everyone) my screen. And every minute that elapses I wish my dad was here more.

I’ll spare you all the gory details, but he died in probably the most horrific and slow way possible. Something no one tells you about having a family who’s “dying” is just how long and short that process is: one minute they are sick, the next you are spending twelve years watching their muscles melt off their bones and their insides liquify. It’s horrible. But if my dad left me anything as a continuation of his legacy, it was his Catholic faith.

I used to resent him for making me go to church every weekend. Honestly, what kid wouldn’t? I had to wake up at 7 am on Sundays, clean myself, make myself presentable, and be dragged from the warmth of my home to Sunday school. I knew how I felt about God, I knew my faith was “unshakeable” (lol child me, meet agnostic teen me, ages 13-16, filled with angst instead of God’s love!) I could not work out why I still needed to physically be in Church every week. For the most part I didn’t question it. My father was not without flaw, and if me or my sister even so much as groaned at the idea of going to Mass, we ignited his wrath.

One day, when I was six or seven or eight and my sister was whatever the crap age where you start questioning all the ideology you’ve been pumped with and get mouthy to your parents, she refused to go to Church. The whole time getting dressed she was grumbling and groaning.

“But I’m tired,” she’d whine.

“Ugh, me tooooo,” I’d parrot back, trying to match her cadence well enough that she’d forget I was five years younger than her and freshly uncool.

Then she got a mischievous look in her eye, the kind I only see now when she’s either had way too much to drink or is about to make a poop joke. “Maybe,” she started. “ We can take a stand. Tell him we don’t want to go, and he can’t make us.”

So when we were dressed, we trudged out into the living room of our two bedroom apartment and stood in front of him.

“Ready to go?” he asked, keys in hand, eyes trained on the Sunday morning news.

“Yes!” I squeaked out. My sister glared at me and rolled her eyes. This is why little sisters are uncool, I assume she was thinking.

As we rode down the elevator, I could sense her steeling herself to make the declaration. She was going to stick her neck out, maybe change life for us moving forward, give us Sundays where we could sleep in!

We approached the entrance to the garage and my sister hung back.

“Monica, what is wrong with you?” My dad asked. He hated being late anywhere, especially church.

“I don’t wanna go to church,” she said. “I wanna go back upstairs and sleep.” Her stance was strong but her voice betrayed her uncertainty. I think that’s where she went wrong; if my dad smelled weakness, he pounced.

This time, he threw his keys on the ground and stamped his foot. He shouted a lot, many words one wouldn’t expect to hear spoken to children on the Lord’s day, but it was the last thing he said that really stuck in my mind.

“Do you want to become a pagan?” Tears closed his throat so that the last syllable of that word was almost a squeal.

I thought immediately of Moses standing at the bottom of the mountain, having thrown the tablets carrying the Ten Commandments into the effigy of the Golden Calf. He watched with no remorse as the ground swallowed up his former followers, the wind flapping through his robes. My sister and I always joked about my dad being angry like Moses, but in that moment, I could really see it. I imagined that he showed us that movie every year, not just because it happened to be on TV, but because he saw himself in this biblical figure, the thwarted Prophet who never made it to the Promised Land.

Easter was the last holiday we had with him that was normal. Even though he couldn’t stand for long periods of time, we drove the twelve minutes from our house to the beautiful church I’d grown up in, and sat through the first two hours of the French (read: African) Easter mass. I watched my dad grow more and more exhausted as the service progressed until, right after we took communion he ushered us out so he could go home and rest. It was the last time I saw him normal, the last time I saw him as the father I’d known my entire childhood. Within a month he could no longer leave the house, and by the early summer he couldn’t walk anymore.

It’s been six years since my last Easter with my dad. Before he died, but especially since he passed, this has been the most important holiday of my year. Today, I’m trying to pass down the tradition to my niece. Maybe one day she, like me, will remember how we watched Charlton Heston—stunt queen extraordinaire—pretend to be the liberator of Israel.